Turns out people have strong opinions about snow days.

Recently the New York City Department of Education released their calendar for next year and, in addition to declaring that Columbus Day will now be called Indigenous Peoples’ Day/Italian Heritage Day (the most awkward combination of two things since a Taco Bell/Pizza Hut), also announced they were eliminating snow days. If it snows three inches, students now have Zoom school.

People were not happy. Social media erupted, of course. A few friends from outside NYC texted me about it. (“You monster,” wrote one.) But more curiously, this became national news. CNN ran a story. And the Washington Post. And USA Today. And the Wall Street Journal. And BBC. Even a radio show in New Zealand, of all places, covered this breaking news event, and also a local news station in frosty Tampa. Most of the stories were written with an incredulous tone -- perhaps a touch elegiac, even -- and uniformly included quotes and Tweets from irate parents and educators who acted as if childhood itself had been declared illegal.

And here’s Michelle Goldberg, with no apparent irony, in the New York Times: “It seems like callousness bordering on cruelty to scrap one of childhood’s greatest pleasures in favor of a rehash of pandemic life.”

“Cruelty.” Got it.

Though I have fond memories of snow days myself, I was a tad confused by the collective howl to this announcement because, well, snow days in the city just aren’t that much fun. Aside from the fact that snow remains pure here for about an hour before the dog walkers defile it and cars churn it into a garbage Slurpee, you don’t see hordes of stocking-capped kids sledding down hills or building snowmen in their front yards because there aren’t that many hills and there aren’t that many front yards.

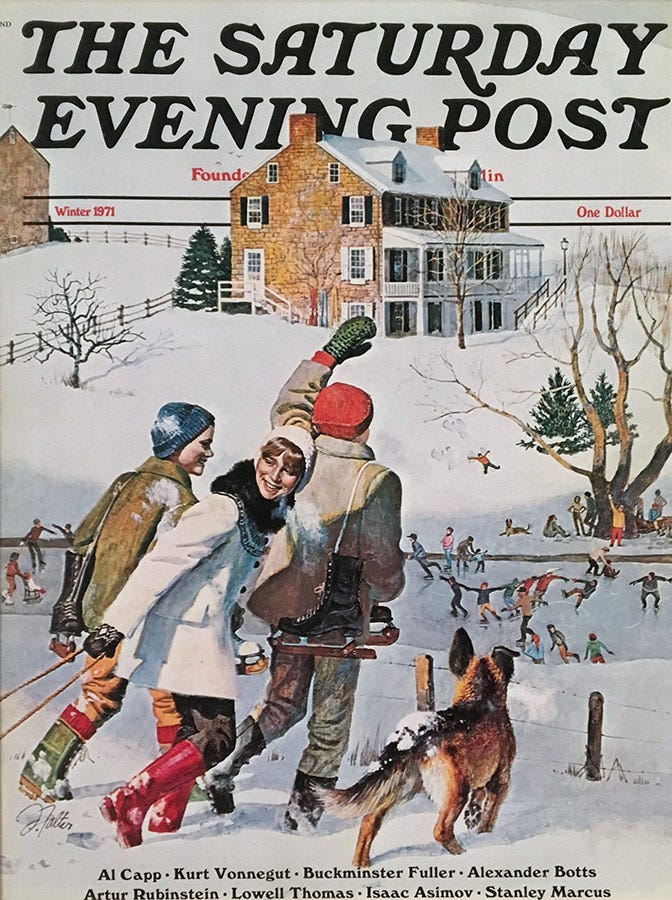

Plus, some of the factors that made the pandemic so miserable for a lot of city kids, especially those in poorer households, are the same factors that make snow days kind of a bummer: small apartments, crowded with relatives, not super close to a nice park or playground. So while “snow day” for many people may evoke a Saturday Evening Post cover or a Campbell’s Soup commercial, when it snows four inches in the Bronx, the more accurate depiction is image is from the Ashcan School, with kids marooned indoors, away from their friends, babysitting their siblings, staring for hours on end at their phones.

Robert Henri, "Street Scene with Snow (57th Street, NYC.) Famous painting from the Ashcan School.

I mean, who’s ever seen a snow fort in Chinatown?

And why isn’t this disconnect more obvious to everyone?

Part of it, duh, is that not everyone lives in the city. A larger part, still, is that most people (especially those who write about education, ahem) aren’t intimately familiar with what poor kids’ lives are like day-to-day.

But an even greater cause for the dismay behind the cancellation of snows days is due to something we could call the Universal Fallacy in Education.

This is the fallacy that leads people to believe that school should be a certain way for everyone else because school was a certain way for them.

It’s why most of us look askant at home school. It’s why so many parents hate “Common Core Math” and think schools are teaching multiplication all wrong. It’s why the idea of year-round school can feel like a violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Or why people of a certain age are positively shocked when they find out schools don’t teach grammar anymore. (Relax. Most do. Just in a different way.)

And it’s also why the same set of books show up on survey after survey of high school English reading lists: To Kill a Mockingbird, Romeo & Juliet, The Great Gatsby, Of Mice and Men, Night, The Crucible, Julius Caesar, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Animal Farm, Macbeth, Scarlet Letter, A Raisin in the Sun. And even though English classrooms have changed quite a bit in the past 15 years -- there’s a greater emphasis on argument and non-fiction than when you were in school -- and though the high school canon has become far more inclusive — Toni Morrison and Amy Tan are are on there, but so are Malcolm Gladwell and David Sedaris — this list, by many accounts, has been relatively stable for decades.

Anything wrong with those books? Nope. It’s not the books themselves that are the problem. It’s how those books are chosen that’s the problem.

Read this, from an editorial in the journal, English Education, titled “Thinking Deeper About Text Selection:”

Another important—and often unstated—factor that affects text selection is what teachers are familiar with [. . .] and feel comfortable teaching. This set of texts can be traced directly to the kinds of courses that preservice teachers take in either their undergraduate or graduate English/English education programs and to the texts that they have studied in junior high and high school English classes.

Meaning that a lot of high school English teachers are just assigning books they were assigned themselves. Meaning they’re choosing books out of convenience, not because they believe those books will be best for their students. “I remember how much I loved reading Lord of the Flies in Ms. O’Shaughnessy’s class in 10th grade, and so you’ll probably like it, too,” you can imagine the rationale going. This is the Universal Fallacy in Education.

You can see this fallacy beyond the English classroom, too, when teachers recycle curriculum from previous years without making any major changes, or rely too heavily on textbooks, or teach in the way they were taught, or when school leaders try to implement an intervention that worked at another school1. But as education thinker Dylan Wiliam has become famous for saying, “Everything works somewhere; nothing works everywhere.”

In other words, schools are not Lego sets. They are not comprised of small, interchangeable parts that can be easily snapped into place. They’re more like that scene in Apollo 13 when the harried engineer walks into the room and tells the other engineers that they have to figure out a way to save the stranded astronauts by only using what they’ve got on board the spacecraft, and then he dumps out on the table a random assortment of junk — hoses and straps and a space suit — and they have to literally design a method to fit a square peg in a round hole. (Spoiler: they succeed, the astronauts survive, and Tom Hanks wins his 24th Oscar in three years.)

If there can be only one principle undergirding successful classrooms and schools, let it be this: teach to the students in front of you. Meaning, you must know them, you must constantly check to see if they’re picking up what you’re putting down, you must adapt. If all it took to educate kids was a human standing in front of them talking, school would look a hell of a lot different. It wouldn’t cost us so much, either. We could just dump kids into stadiums and turn on the Jumbotron. But because schools are the most dynamic, unstable environments on planet earth (seriously!), and filled with unpredictable smelly little imps we euphemistically and affectionately refer to as “students,” and depend on positive working relationships among biblically flawed creatures we generously call “adults,” and are also vitiated by external factors more than we’d all like to admit, you can’t teach geometric transformations the exact same way 5th period as you did 1st. You can’t just take the curriculum you taught at West Meadows High School and teach it at Frederick Douglass. You shouldn’t teach Romeo and Juliet just because that’s what you read in 9th grade.

There is no copy and paste. That’s what makes it so goddamned hard. (And fun.)

One final observation before I connect this back to the Untimely Demise of Snow Days: Public school is the only thing most Americans have in common2. And whether you sat in the front row and pertly reminded the teacher that she forgot to collect everyone’s homework, or you sat glumly in the back and counted down the minutes until 3 p.m., almost none of us had completely terrible experiences in school, especially since “school” is not actually a place, but a process that happens over the course of 15 years. Thus, whether we openly admit it to ourselves or not, school means a lot to a lot of Americans, and most of us, intuitively, understand how critical the public school is to the American experiment. And because “over long periods of time schools have remained basically similar in their core operation,” writes David Tyack and Larry Cuban in Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform, “these regularities have imprinted themselves on students, educators, and the public as the essential features of a ‘real school.’” In other words, then, we’re all protective of school, we believe in school, and so we expect it to be a certain way.

Hence, the dismay from so many people that snows days in New York City (and other districts) have been canceled. School, the big takeaway is, will not be the same as it was when they themselves were in school.

But by accepting the principle that we should teach to the students in front of us, and by rejecting the Universal Fallacy in Education, we might have an easier time assigning Fences instead of King Lear.

We might also easily accept that getting rid of snow days might actually be the sensible decision. That it might actually be the more equitable one, too. And that, in any case, for students who depend on school for so much — food, safety, structure, socializing, learning — snow days may not have been “one of childhood’s greatest pleasures” anyway. And, finally, that we must not let slip from our grasp any opportunity, however small or seemingly unfortunate, to add to the achievement of our most vulnerable students.

Equity must always trump nostalgia.

Most snowmen are ugly, anyway.

Photo source (top): John Falter, The Saturday Evening Post, Ice Skating in the Country, Winter 1971; https://mona.unk.edu/mona/john-falter-mona-collection-gallery/1986-32-900

Photo source (bottom): Robert Henri, American, 1865–1929, Street Scene with Snow (57th Street, NYC.) Yale University Art Gallery