Is Teaching Novels Even Worth It?

Book bans are dumb, but the indignation they evoke is misguided.

A version of this story appeared on Alexander Russo’s The Grade.

So, I guess we’re banning books again.

My first reaction is confusion.

Why would anyone complain about a YA novel that “depicts sexual activity” when the actual search history of any 13-year-old boy’s phone would make his parents’ eyes melt? And why are people so angry about the bans, which are clearly symbolic? (After all, no one’s starting bonfires.)

But most of all, the feeling I’m left with is dismay.

Dismay that, yet again, a major education issue dominating the news reveals just how little everyone understands or is willing to say out loud about what actually happens inside most American classrooms.

And the most common reaction from educators when they hear about another book banning isn’t indignation. It’s a shrug.

All that said, I’m no fool. As the pandemic occupies less and less of our collective attention, and as we near the midterms, there will be more book bans. And there will be more coverage.

That being the case, these stories might as well benefit from insights into how books in high school and middle school classrooms are actually taught. These insights might mitigate the alarmist tone that often inflects these stories.

But more importantly, they will also remind readers (and the reporters themselves) that some of the largest obstacles to learning in American classrooms are rather mundane.

As reporters continue to report on these bans, they should point out that not all of them are the same and that the complexity of novels, students’ tendency to avoid assigned readings, and the logistical challenges of teaching long books can complicate our romanticized notion of what actually happens in classrooms — and what presents a real threat.

1. Not all bans are created equal

To begin, reporters should distinguish between the two main types of bans: books yanked from library shelves and books struck from a curriculum.

The sheer volume of books in a library and the near certainty that any supposedly objectionable viewpoint or theme found in one book will be found on another shelf nearby (or online) means that bans that target library titles are more than likely symbolic and therefore probably politically motivated.

This might be a moot point to those who see all bans as existential threats, but practically speaking, banning books from school library shelves won’t achieve their stated ends, and as such, don’t warrant as much coverage as bans that target books from a curriculum.

2. There are 13 ways of looking at a blackbird.

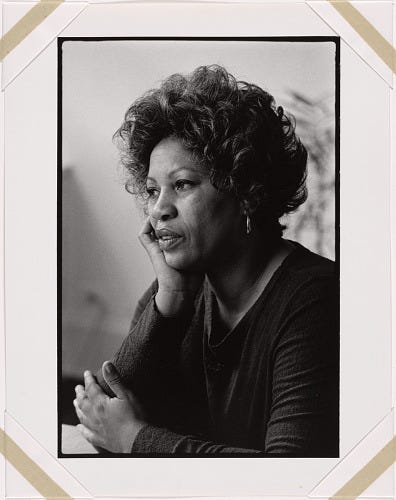

Which is not to say bans that go after books meant for a curriculum — like the recent challenges to Toni Morrison’s Beloved — justify breathless coverage.

In these cases, reporters would do well to remember that, as poet Wallace Stevens reminds us, there are 13 ways of looking at a blackbird.

If a parent takes issue with a particular scene or theme in a novel, we should not assume that scene or theme is going to be taught. That is, how books are read in school — selectively, with great difficulty — is not the same as how we adults read them.

This insight is obvious to educators but probably odd or counterintuitive to everyone else.

Novels lend themselves to multiple interpretations — what English teachers fondly call “themes.” Novels may have dominant themes — the comprehensive destruction of slavery on the self in Beloved, e.g. — but no novel demands the reading of one theme to the exclusion of all others.

How a teacher decides to teach a novel is a deliberate choice that depends on a constellation of factors: the teacher’s interest or capability; the age, skill level, interests, or background of the students; the learning goals of the unit; and the unifying theme of the curriculum, among others. Add time constraints and how little students actually read (more on that in a minute) and not every chapter or scene is discussed or even read because not every chapter or scene needs to be. No two teachers will teach To Kill a Mockingbird the same way, and as odd as this sounds, you could still do that novel justice without focusing on the racial theme, and many teachers do. (Whether that’s a good idea or not depends on the aforementioned factors.)

So, when a parent mounts a complaint about a book, reporters would do well to investigate how or even if teachers will be addressing that theme.

Talk to the teachers or the department chair. The controversy may be full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Stories should note that.

3. Kids won’t eat their broccoli.

Aside from the teaching of writing — which includes the exhausting (and, depending on how you do it, utterly pointless) task of providing meaningful feedback on student work — I would say that teaching a novel well in an English class is, logistically speaking, the most difficult thing a middle school or high school teacher will do.

This is due almost entirely to how little students read outside of class.

I cannot stress enough how enormous of an obstacle this presents to the successful execution of a book unit, or in the very least, one that doesn’t drag on for an interminable eight weeks, with the teacher force marching her bored captives to the very last page with entire periods of halting read-alouds and coerced silent reads.

And students’ obstinate refusal to read outside of class transcends class, race, skill, gender, age, and even time. And don’t blame the internet— there was never a golden literary age when most students did not find creative ways to fake their way through reading assignments. (When people tell me fondly that they read The Grapes of Wrath in high school, I think, No, your teacher assigned it.)

What does this have to do with book bans? Many individuals — especially those of us who did well in school (present company excluded), and who often comprise the corps of individuals who grow up to write about school — have a romantic notion of what happens in English classes. Still others have a mistaken notion about what happens in classrooms.

Individual books rarely change students’ lives. The reality is messier and less epiphanic than we remember, or what we see on TV. English classrooms are where great works of literature go to die. As a result, the specter of a book ban can seem worse than it actually is.

Reporters might talk to teachers, department chairs, or administrators about how novel studies in their school actually go. Reporters might talk to concerned parents, too, about how they think book units go. Or maybe talk to students about their experiences reading books for school that are now under threat of a ban of some kind. You might be surprised.

4. Don’t mistake the map for the territory

Teachers’ unit plans rarely go according to, well, plan. There are exactly 10 trillion possible things that can happen to interrupt the seamless progress of a unit, and at least 15,000 of them happen before the end of your first class.

What’s more, the variety and quality of units is pretty vast, so one class’s reading of Romeo and Juliet may amount to passively watching clips from the 1996 Baz Luhrmann movie while answering questions on a worksheet, while others may have them act out the scenes, while still another’s may engage students in a close analysis of the play’s punny language.

One idea for reporters is to follow up when a book has been targeted for a ban. Ask for the unit in question and observe a few classes of the book being taught. Are the classes following the trajectory planned for in the unit, or did the teacher change course?

Effective teaching is as much the result of careful planning as it is of flexibility. Good teachers know what they’re doing in two weeks, but great teachers don’t know what they’re doing tomorrow.

Look at student work and ask students about it. Then tell your readers what you saw or learned.

Pry open that black box.

All of this, then, is not to suggest that the messy, unpredictable dynamics of classrooms render book bans absurd because hardly any learning gets done and who cares about books, anyway.

On the contrary, these four points are to remind outsiders, especially journalists who write about education, that the messy, unpredictable dynamics of a classroom demand we question our impressions of what we think happens in classrooms.

The claims about American classrooms implicit within book bans oversimplify the reality. Our own memories of school can all too often romanticize that reality, too.

Classrooms are a black box, but reporters can pry them open, with care.

What they show us might worry us, but I can guarantee it’s never as bad as what the harshest critics believe. And we might see that there are actually bigger problems to solve.

Above image: Toni Morrison, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Helen Marcus, 1978

THANK YOU for this article! I've never been happier I found your Substack.

I really appreciate the point about divergence of classroom experiences, and I hope in your note to reporters that a lot of deep digging can drag this specific problem into the light.

I also appreciate the reminder about the difference between library bans and curriculum bans. As a student, the curriculum bans actually worry/worried me less, because I didn't *want* to read those books anyway, and they were still available in the school library if I had. A library ban keeps that book out of a reader's hands.

Worse still are the all too common shadow bans where librarians (either themselves or under the direction of a higher power) remove books from the school or local library. I spent some time volunteering at both my high school and my community library as a teen, and these were a real thing. You may wish to address this kind of situation in an addendum to this post.

The "bigger problem to solve" is exactly the point in most banning efforts, IMHO. Sure, parents are interested in how their children are educated, but realistically, they can't devote large chunks of time to fully understand the nuts and bolts of classroom dynamics. They see that a book (either in the library or on a required reading list) contains hot-button issue content, with which they disagree, and they act to prevent their child's exposure to it. I haven't studied the details of what recent banning efforts have attempted to ban, but I suspect that most efforts these days center around two bigger problems: 1) What material is proper to expose to a student of a particular age, and 2) The question of whether the school or the family should determine the exposure of certain topics to the child.

In the cases I have seen, these two problems often go hand in hand. A parent sees that a book being read to her six year old son advocates faddish New Age gender material and reacts negatively because she believes that her son is too young to adequately absorb the lesson, beyond an indoctrination level. She also believes that it is her job to determine when and how, her son is exposed to the issue. Both concerns have legitimacy, and the upshot is that she demands that the school remove the book. She doesn't parse the nuances of educational theory, but she knows that her plan for her child is being challenged. She probably also believes that other, similar challenges exist in the system and she sees this book as a point of contact with that system for which she may have some influence. The same analysis can be applied to a book in the library that is accessible to her 13 year old daughter that demonstrates approval of a lifestyle that she wants to discourage.

Of course, bans should not be imposed at the drop of a hat and should not be successfully driven by the lunatic fringe. But there are legitimate concerns about the influence of academia on young minds, and those concerns do not need to be centered in the pedagogy to be valid.