School Start Times, the 1619 Project and Warby Parkers

Apparently no one understands what actually happens in schools.

Just a quick public service announcement. If you like what I’ve been doing, please subscribe! And please forward this to someone else who you think might enjoy these posts. AND OR please sharing this on Facebook, Twitter, Friendster, wherever. I \ missed my subscriber goal for April (by only a few! just a fewwwww!), so I’m hoping to make that up in May. Thank you for reading.

Looks like it’s tutoring.

Summer school, longer school days, an extended school year, and beefed up at-home reading programs have all been identified as solutions to mitigate the learning loss our kids have endured this past year, but the one that supposedly works best? It’s tutoring, baby.

But it’s pricey. Because tutoring doesn’t work if you just sit a few kids in a classroom with a teacher after school. Glorified study hall this ain’t. Nope. You’ve got to do what’s called “high-dosage” tutoring: two or three students working with one (trained) adult almost every day, during the school day, for months.

To which I say: Well, duh.

If there’s one sure fire way to boost academic outcomes it’s . . . school. And more school usually leads to . . . more learning. Who’d a thunk.

Forgive my flippancy. I don’t mean to poo-poo the outstanding research bolstering this finding, including and especially that of the late Robert Slavin, who died last month, and who, as a BFD researcher (in education), has been instrumental in moving schools away from our embarrassing over-reliance on woo-woo pedagogy and junk science and toward evidence-based practices instead. (Check this out for more on that. Or just Bing “Learning Styles myth.”)

So, yes, even though it is extremely obvious to any educator who has found that teaching to fewer kids is usually more effective than teaching to many kids, and that more classes is usually better than fewer classes (so, all of us), I’m skeptical. But not of the evidence. Just the promise of tutoring as a winning solution.

It’s the same reason I am skeptical of a study that came out last month that found students’ GPAs increased after the district pushed back the school start time. (Found to be true elsewhere, too.)

And it’s the same reason I’m skeptical about this Baltimore program that claims giving free Warby Parker eyeglasses to poor kids led to significant increases in reading scores.

And why I remember thinking that the mindfulness craze as a promising academic intervention was wishful thinking, and why I wasn’t terribly surprised when the 1:1 laptop initiatives (one student, one laptop) didn’t pan out.

Not because I think starting school later, free eyeglasses, a little nirvana or laptops are a bad thing! Of course not.

It’s just that, whenever you read about these solutions, there’s always this implication, however faint, that this solution is the one that will narrow the achievement gap, if even just a little bit. This this solution is going to give to poor kids something they’ve long been deprived of— this one easy fix, and now that they’ve got it, now that we know what it is, welp, they might just be alright. Scale up and bye bye, intergenerational poverty.

Eyeglasses? And first period that starts at 8:45 instead of 8:15? That’s it?

To be fair, no one ever claims these solutions are silver bullets (well, almost no one), but even the promise they supposedly have to improve outcomes for the hardest-to-teach students always leaves me wondering when the last time was that these researchers or journalists spent any time in a school.

The same goes for everyone currently losing their minds over the 1619 Project. (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, here’s a primer.) I know Tucker Carlson has been in high dudgeon about this for a while, but based on the burst of texts and emails some of my friends and colleagues have gotten from inquisitive relatives in the past two weeks -- U dont teach ‘critical race theory do u, just wondering!! luv aunt chris -- I’m guessing Hoda finally did a segment about it on the Today show, or maybe there was something on 60 Minutes.

Every decade or so, this country gets into a heated argument about how we teach American history, or just what malarkey is in our school’s curriculum in general, with one side imagining that all history classes are taught by Fred Hampton while the other side imagines those classes as not too dissimilar to a Hitler Youth Rally, and with both sides thinking the soul of the country and the fate of the United States depends on what you think about Thomas Jefferson.

To which most pragmatic educators think, Not quite.

Meaning, if only we were that good at our jobs. Ha. If only our students listened intently in class, and took notes, and did all their homework, and left class with their eyes open, armed with a new understanding of history, ready to shape the future. If only we had that power to so easily indoctrinate them.

People whose only experience with school is that they once went to school completely underestimate just how little goes according to plan, and, though teachers are loath to admit this, just how little influence one teacher or curriculum ultimately has on a student.

Because schools are enormously messy, almost indescribably so, and whether students learn or not often feels more dependent on some enchanted alchemy than on the talents and skills of the adults in the building, or what the content standards are for your subject.

Here’s an example. Every single teacher has had this experience: you teach a lesson to one class, and it’s amazing, perfect even, the kids learn, and as they walk triumphantly out the door, you picture yourself getting the Congressional Medal of Honor and you think, I am the best teacher on Earth. But then the next class walks in and you teach the exact same lesson and it’s a disaster. A total educational nightmare. For reasons that elude you, zero learning happens, antagonism reigns. You did everything the same! And so as that class walks out of the door, and you look at all the chip bags and worksheets strewn on the floor and briefly reconsider your position on child labor, you think, Horace Mann was a goddamned idiot.

And those days are not as rare as you would think.

In fact, day-to-day, it does not appear that school works. Up close, it often appears like a whole lot of progress is not happening. Your students are still forgetting to carry the one. Mr. Eliot is still asking questions to the whole class instead of cold calling students by name even though his instructional coach has been working with him on that since September. The seniors are still strolling in late, despite the programmer switching English with their study hall. The science department is mulish about including literacy standards in their units even though students are still underperforming on state exams. Oh, and the wifi’s out in the B wing again.

The brilliance of American public school is in the slow, steady indoctrination of students that happens over the course of many, many days, and many, many years, under the care of many, many adults. The pat idea that one teacher, or one intervention (like free Warby Parkers), or one curriculum alone will transform a child is false, for the groundwork for that transformation was laid by a thousand previous lessons and a hundred other teachers, and a million little words and corrections and pieces of feedback, most of which we will all eventually forget, or might not ever see.

And though there’s tremendous variation not just across districts and schools but often within a teacher herself (see above example), everyone involved has the same idea about what we’re supposed to do: make kids smarter -- academically, emotionally and socially. And most of the time, most people aim for that target.

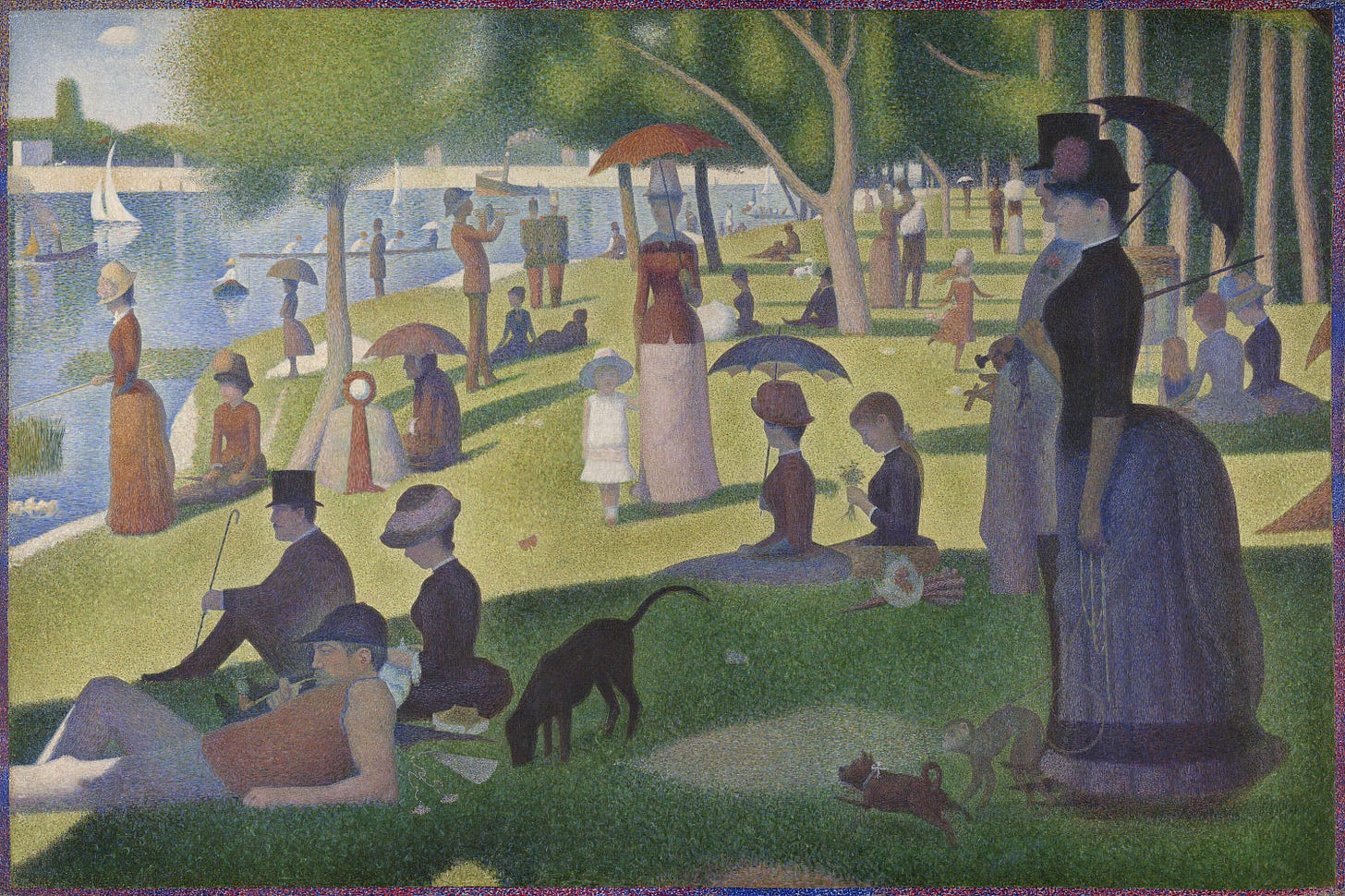

So, it’s pointillism by committee. Sure, there might be quite a few errant dots -- dots that are all the wrong color, or, hell, dots that don’t seem to be dots at all -- but when you take a step back, you can see a bunch of people enjoying a Sunday afternoon.

All of which is not to say that since schools are such dynamic, unpredictable ecosystems, there’s not much we can do to shape student outcomes and so we should just throw our hands up and hope for the best. Hell no. We actually know exactly what do to most of the time.

But students are aircraft carriers, not light switches. So all of this is just to say that there is never one clean line of causation between even a well-researched intervention, like tutoring, and academic outcomes. Or one clean line of influence between one kind of curriculum, and student beliefs. There’s a whole lot of other stuff that happens around it. Be skeptical of anybody who claims the opposite. Schools are a hot mess.

In a good way.

Photo credit: https://api.artic.edu/api/v1/artworks/27992/manifest.json