Are things as bad as they seem?

I started writing this newsletter out of a sense of frustration at much of the education coverage I was reading. The tone of the pieces was, if not negative, then at least somber, and the tropes were nearly always the same: angry or dissatisfied parents; overworked, underpaid teachers; stressed out or bullied children; beleaguered administrators; poor city kids in dysfunctional schools. The subjects seemed to be always struggling against something -- the curriculum, other parents, the district, the “system,” their piteous circumstances -- and though I will concede that school, let’s be quite honest, is basically coercing large number of humans to do stuff unnatural or disagreeable to them (wake up early, read an old poem, add fractions, be nice) and which tends to create friction, much of the time, schools are pretty fun. Maybe not Disney World, but it’s hard not to feel elation when you’re surrounded by hundreds of people working together toward the same positive goal, even if at times it can be a slog. So much of education coverage just didn’t jibe with my own experience, or the experience of my students, or that of my colleagues. I kept thinking, Where’s the positive stuff?

Though many of pieces I’ve written for this newsletter have argued against widely held narratives about American education, I wanted to quantify, with hard data, how negative or positive education stories actually were.

So that’s what I did. Results, above.

I grabbed all of the headlines for the month of August from 8 major publications that cover American education and categorized the tone of those headlines as positive, negative or neutral. This is a crude version of something called “sentiment mining,” and it’s been used to analyze how news sources, in spite of the incredible progress humanity has made in a myriad of areas (health, wealth, disease, peace), continue to paint an overly pessimistic view of the world.

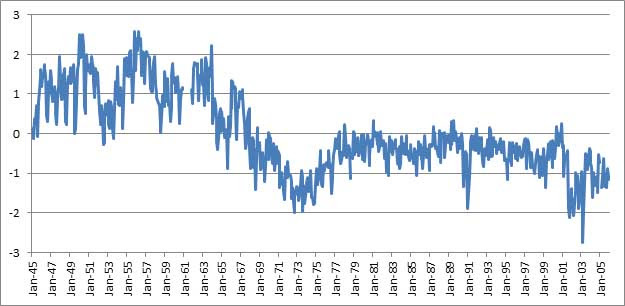

Average monthly tone of New York Times news content 1945–2005. Down means negative. Is the world getting worse? Of course not. Source.

A more thorough explanation of my methodology is below, but the quick and dirty is this: I searched for every education story in the above 8 sources from August 1st to August 28th and analyzed the headlines. I analyzed only the headlines because it would have been impossible for me to analyze the tone of almost 400 articles, but also, reading headlines is mostly how we consume the news at this point. We scroll, we click, we skim. Think of all the social media posts, emails, newsletters, and websites you peruse daily. How many entire articles do you read vs. how many headlines only? I’d bet for every 10 headlines you read, you read 1 full article, and I’d also bet that that’s being conservative.

Thus, our sense of what American schools are like comes largely from what those headlines say, and our feel for what’s going on in American schools no doubt derives from the tone of those headlines. But feelings aren’t facts.

Reader’s Digest is boring for a reason

Now, I don’t presume to know what the optimal balance of good news and bad news is, and it would be silly to argue for quotas or parity. Some news just is bad and some periods of time are worse than others. Into each life some rain must fall. And also, let’s be quite frank, good news just ain’t as interesting as bad news. Editors know this. Thence the hoary cliche If it bleeds, it leads. The late Swedish academic Hans Rosling, writes in Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World - and Why Things Are Better Than You Think, that “media can’t waste time on stories that won’t pass our attention filters,” which prefer drama and variety, and which is why an editor would never approve a headline that read MALARIA CONTINUES TO GRADUALLY DECLINE or METEOROLOGISTS CORRECTLY PREDICTED YESTERDAY THAT THERE WOULD BE MILD WEATHER IN LONDON TODAY. Psychologically, for humans, bad news just hits us stronger than good news. “Bad is Stronger Than Good” is the forthright title of a famous paper that describes this phenomenon; we remember bad more, we react to bad more, we sit with bad more. That also explains why gossip -- by definition salacious, tawdry, negative -- is so irresistible, and also why we love reading novels (which are centered on conflict), and why Reader’s Digest, so indefatigably sunny, is such a bore.

Glaciers sprint

But the news, as has been observed, is the first draft of history, and at this point, with our news cycle spinning at an hour-by-hour basis, it’s impossible to see larger trends, slow-moving progress, reversals and even corrections of errors. (Remember Richard Jewell?) As a result, newspapers, websites, and magazines frequently fail to report, well, reality. As we doom-scroll and refresh, refresh, refresh we in turn fail to see the forest through the trees. “If news outlets truly reported the changing state of the world,” Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker writes in his book Enlightenment Now (quoting economist and philosopher Max Roser), “they could have run the headline NUMBER OF PEOPLE IN EXTREME POVERTY FELL BY 137,000 SINCE YESTERDAY every day for the past twenty-five years.” But that doesn’t quite qualify as news. Instead we get snapshots. And snapshots only tell a small part of the story. (Remember the famous smirking photo of the Covington Catholic boy?) Stare at a glacier for a day and it’s a statue. Stare at it for a million years and it’s sprinting.

This is just to say

All of this is to say that I understand why the news leans negative. I also understand these publications are businesses that rely on our attention, and that it’s in their financial interest to get our attention.

But.

I might question the ethics of publishing too many the-sky-is-falling stories when there are children involved. The problem with overly negative coverage is that it overstates or isolates problems, distorts reality, takes statistics out of context, and/or pulls our attention in the wrong direction. (Some stories, too, are just pointless. The USA Today and the Washington Post both ran a story this week on a school district in Waukesha, Wisconsin that dropped a free lunch program because the school board thought it would “spoil” children. Sorry, but who gives a fuck? The Waukesha school district has 14,000 students. Why is this of national interest? What is the value of this story outside of garnering those outlets a few more clicks and stoking outrage?)

Just a friendly reminder here that schools aren’t just buildings close to our homes that we send our children to every day. They are America. I don’t mean that in a symbolic sense. I mean that literally. Schools are where America happens. Schools are how America happens. We have a unique, messy system that allows for all of us to participate in and shape its critical mission of preparing children for the future, which is, ya know, our future. But if we do not have a clear, accurate understanding of what is happening within those buildings, how can we be expected to help where the help is needed most? I might also add that overly negative coverage has other consequences, too. It creates monolithic groups of students who we assume have common, piteous circumstances, or are absolute hellions to teach. (This explains why so many people, when they find out I work in an urban public school, either somberly thank me for my service as if I’m an amputated war veteran, or furrow their brows as if I’ve just told them I’m planning to get a full face tattoo.) Most parents, too, don’t seem to really understand what makes a “good” school or district, and so end up choosing ones for wrong, often odious reasons (like the socio-economic makeup of the student body, or how great the sports fields look). This exacerbates inequality by pulling money and political power away from the most vulnerable students. I’m not blaming the media for the achievement gap, of course, but given how much the media shapes our understanding of the world, it would be silly not to hold newsmakers at least to some account.

No, what I’m attempting to do here is simply question whether education news needs to be as non-positive as it is. Alexander Russo, education news’ unofficial ombudsman, has also thoroughly noted how “alarmist” and inaccurate so many of the “scare stories” are.

Are there really so few bright spots out there? Is there actually that much trauma? Is school in America really such a chaotic, unmitigated hell for so many people?

Decide for yourself. Look at the data. What do you see? As teachers love to ask to the irritation of students everywhere, what are your noticings? Is there a surprising difference among sources? Is there a bias one way or another? Is that bias understandable? If you’re a parent, does the bias in the data reflect the experience of your child at his/her school? What about the other kids at his/her school? What about his/her teacher? Or the administrators? Or the school aides? If you’re a teacher, does the imbalance in the data reflect your own experience in your classroom? What about your students’ experiences?

Are things as bad as they seem?

Methodology

I analyzed the headlines from the major news publications that provide national education coverage and categorized them as negative, positive or neutral based on the language of those headlines. I decided to look exclusively at the headlines because there was no feasible way for me to read and categorize 400 news articles. Any headline that included words or phrases that evoke discord, anxiety, turmoil, stress, fear, anger or sadness -- “School Is Back in Session in Atlanta. Teachers and Families Are Wary” -- was categorized as negative. Any headline that included words or phrases that evoked comity, happiness, success or striving -- “When Teachers and School Counselors Become Informal Mentors, Students Thrive” -- was categorized as positive. Headlines that indicated neither -- “We Studied One Million Students. This Is What We Learned About Masking” -- were marked as neutral. I tried to stay as non-partisan and content-neutral as possible. So, though the headline “Los Angeles and Chicago schools will mandate teacher vaccinations” is in my opinion, positive, because disease = bad, there’s nothing intrinsically positive about the language of the headline — it evokes no emotion — so I categorized this as neutral.

I grabbed the headlines from the websites of the publications, or, in one case, from a database. I only chose headlines that were about K-12 education, and I did not look at television news, and I excluded any publications (such as The Atlantic and the Wall Street Journal) that I deemed had too few stories. I also excluded trade publications such as ASCD, Education Next, The Kappan and Edutopia. I focused on news and commentary, and shied away from special reports, blog posts, short briefings, videos, and photo essays.

A big ol’ nota bene: This is the first time I’ve done this. I absolutely made mistakes. I maybe missed a few stories, or miscategorized a few. If you spot anything amiss, or think there’s a publication I should have included, or if you think this whole endeavor is stupid, please let me know at oncafeteriaduty@gmail.com.

If you want to check my work, the full list of headlines and my analysis of each are here.